Fall brings the World Series, lots of football games, and–it would seem–almost as many reports on education. Here’s my summary of four recent studies, with close analysis of the most controversial, a study of Michelle Rhee’s IMPACT program in Washington, DC.

These reports claim 1) The teaching force is more qualified than it was 20 years ago; 2) The nation is getting tough on teachers and teacher education; 3) The skill levels of many American adults leaves a lot to be desired; and 4) Getting tough on teachers works. With your permission, I will attempt to unravel these threads and, let’s hope, find a common meaning.

1. The teaching force seems to be more qualified academically. The average SAT score of new teachers climbed 8 percentage points between 1993 and 2008. That’s the takeaway from a new study from researchers Daniel Goldhaber and Joe Walch of the University of Washington, published in the magazine Education Next. This is surprising{{1}} news, given the rash of criticism of teachers and teacher training, including the slam from the National Council on Teacher Quality (controversial rankings) and a tough op-ed by Bill Keller in New York Times. He called teacher training programs “an industry of mediocrity,” a fairly typical example of the lack of respect shown schools of education.

2. Consistent with the rash of criticism of teachers, a public policy has emerged. 35 states now tie teacher evaluations and tenure decisions to student test scores. That’s the big takeaway from the National Council on Teacher Quality’s “state of the states” report. This follows a prior overview by the same organization in 2011. Thirty-five states are now tying teacher evaluations — and tenure decisions — to student test scores. NCTQ wants more of this. “Get tough on teachers” is a pretty common mantra these days.

3. But it’s not just today’s students that (apparently) are being failed by their teachers. American adults aren’t doing all that well either. Should we blame their teachers? In math, reading and problem-solving using technology, American adults scored below the international average on a global test called PIAAC and released by OECD.{{2}} (OECD Survey of Adult Skills) In fact, nearly three out of 10 American adults (28.7%) perform at or below the most basic level of numeracy, compared to around one in ten in Japan (8.2%), Finland (12.8%) and the Czech Republic (12.8%). We ranked below Italy (31.7%) and Spain (30.6%). The study covered 20 countries and tested 166,000 people between the ages of 16 and 65. These skills are, of course, widely considered to be essential for America’s economic strength and global competitiveness.

In other words, whatever’s wrong now has been wrong for a while. The Associated Press has a good summary of the PIAAC report here.

US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan issued a statement saying that the country needs better ways for adults to upgrade their skills. Otherwise, he said, “No matter how hard they work, these adults will be stuck, unable to support their families and contribute fully to our country.”

While that’s undoubtedly correct, my reaction is different. I think the data indicate that most of what we have been doing in the name of school reform for the past 30 years has been off-target–and perhaps misguided. I say that because the PIAAC data reveal how much social background matters, and how little difference schooling seems to make. In the PIAAC study, for example, those whose parents were college-educated did better in both reading and math than those whose parents did not complete high school. Here in the US we talk about ‘the achievement gap,’ ignoring the fact that social class, parental income and parental education–not ‘teacher quality’–are the chief determinants of that gap.{{3}} And what we are doing in schools is, by and large, not closing the gap.

This is not to say that schools don’t matter or that education cannot change lives. What happens in classrooms matters, which suggests to me that we ought to re-examine what we are doing.

4. “Getting tough” on teachers works, or maybe it doesn’t. That’s the takeaway from a study by professors from Stanford and the University of Virginia, who asked whether IMPACT, {{4}}Michelle Rhee’s controversial teacher rating system, was having an impact.

NCTQ was, predictably, enthusiastic: “Yes, says a new study released today. Incentives, Selection, and Teacher Performance: Evidence from IMPACT, by James Wyckoff and Thomas Dee found that the IMPACT evaluation system implemented by Michelle Rhee during her tenure as DCPS Chancellor is indeed raising the performance of teachers.”

Current DC Chancellor Kaya Henderson also hailed the research as evidence that IMPACT is working. “We’re actually radically improving the caliber of our teaching force,” Henderson told The Washington Post’s Emma Brown.

Professors Wycoff and Dee report that low-rated teachers were more likely to resign and that highly-rated teachers were more likely to work harder to try to win the financial rewards the system promises. In other words, it’s a win-win: the (supposedly) bad teachers left, and the (supposedly) good teachers got better IMPACT ratings and a bonus.

However, the study itself is full of caveats, such as “A notable external-validity caveat is that the workforce dynamics due to IMPACT may be relatively unique to urban areas like DC where the effective supply of qualified teachers is comparatively high.”{{5}}

And the study conspicuously does not say whether student performance improved, only that IMPACT ratings did. {{6}}

Mary Levy, a thoughtful analyst who is often asked to testify before the City Council on education matters, believes that the report is “highly misleading,” adding that “The report was worded carefully to avoid stating explicitly any assumption that the ratings system is valid.” Or as analyst Bruce Baker put it, “Put simply, what this study says is that if we take a group of otherwise similar teachers, and randomly label some as ‘ok’ and tell others they suck and their jobs are on the line, the latter group is more likely to seek employment elsewhere. No big revelation there and certainly no evidence that DC IMPACT ‘works.’”

Ms. Levy has done a deep dive into the data, and her analysis reveals what the researchers apparently ignored: the impact of social class and income. Through this lens, IMPACT emerges as deeply flawed.{{8}}

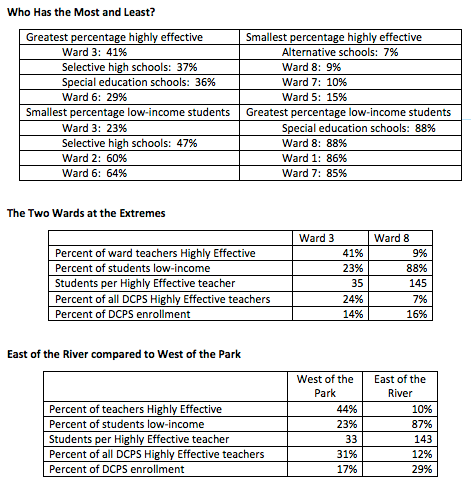

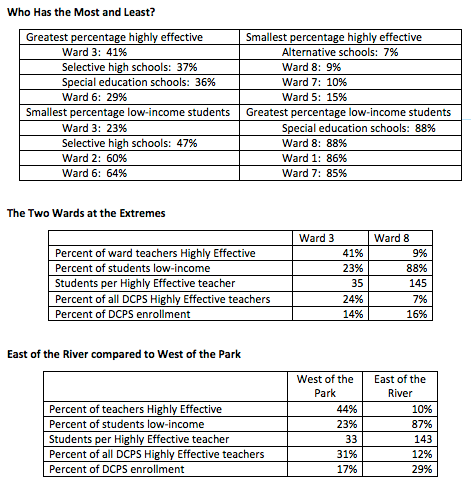

Below is the distribution of ‘highly effective’ teachers in Washington. You need to know that Ward 3 is Washington’s wealthiest region by far, populated by upper middle class families. Only 23% of students in Ward 3 schools {{9}} are low-income. By contrast, Ward 8 is one of the poorest parts of the city; 88% of students in Ward 8 schools are low-income.

Now look at the teacher effectiveness ratings. 41% of teachers in Ward 3 were rated ‘highly effective,’ while only 9% of Ward 8’s teachers made the grade. Ward 3 had one ‘highly effective’ teacher for every 35 students, while the ratio in Ward 8 was 1:145.

The city is also roughly divided by Rock Creek Park and the Anacostia River. Upper income families are far more likely to live West of the Park, and 44% of teachers West of the Park were ‘highly effective.’ East of the River, where 87% of students are low income, only 10% of teachers earned that distinction. Just 23% of students who go to schools West of the Park are low income. The correlation is pretty obvious, and while correlation is not causality, the implications are tough to ignore: If you want to be a highly effective teacher in Washington, choose your students carefully! On the other hand, if you want to increase the chances of losing your job, teach poor kids.

DCPS: Distribution of Highly Effective Teachers {{10}}

Now let’s come full circle. What this study confirms are the findings of the PIAAC study of adults: when it comes to schooling, social and economic status are the greatest determinant of educational outcomes.

It doesn’t have to be that way, because schools and teachers can make a difference. But when the system is narrowly focused on scores on bubble tests–as ours is–and on holding teachers ‘accountable’ for results–as we increasingly do–all bets are off.

—

[[1]]1. Some have predicted that the growth of high-stakes testing would drive competent college students away from teaching. That has not happened, the report says. “We find that new teachers in high-stakes classrooms tend to have higher SAT scores than those in other classrooms, and that the differential in teachers’ SAT scores between the two classroom types grew by about 6 SAT percentile points between 1993 and 2008. Test-based accountability greatly increased after the 2001 passage of NCLB, but we see no evidence that more academically proficient teachers entering the workforce in the year immediately following graduation are shying away from (or at least are not being assigned to) high-stakes classrooms.”[[1]]

[[2]]2. PISA stands for Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. OECD is the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.[[2]]

[[3]]3. It doesn’t have to be this way, of course, but as long as we remain obsessed with test scores, efforts to ‘close the gap’ will fail. I think we may see more protests against standardized testing this school year, following last year’s refusal by some Seattle teachers to administer a test. California seems to be the epicenter of concern and action. Its efforts to eliminate some tests required under No Child Left Behind have produced a stern warning: it could lose as much as $15 million in federal education aid if it fails to toe the line. John Fensterwald of EdSource has a good summary here. [[3]]

[[4]]4. Under IMPACT, which Rhee put into effect during her second year, teachers are rated on a 1-4 scale, with student test scores counting for half the rating, and observations by trained specialists from the central office counting for most of the rest of the score. Get a ‘1’ and you’re fired, whether tenured or not. Rhee’s successor changed the system slightly, and now student scores count for just 35%. The flaw in this approach, as most veteran teachers know, is that teachers switch to the special “demonstration lesson” that they keep handy to impress observers. This is often done with the knowledge and complicity of the students, I’m told. Over the years, I have observed enough observations to be convinced of the unreliability of the approach.[[4]]

[[5]]5. This prose is worse than the usual education-speak because it’s also bad grammar: Nothing can be ‘’relatively unique.’ Just as the female of a species cannot be ‘a little bit pregnant,’ there are no degrees of uniqueness. A thing is unique–or it is not.[[5]]

[[6]]6. I asked Thomas Dee, a co-author, for more information, and he graciously replied as follows: “I think the “plain English” takeaway from our study is something like: The incentives embedded within IMPACT improved teacher performance and encouraged the voluntary attrition of low-performing teachers.

I’m seeing at least two issues about this takeaway that seem confused in the public discussion so far.

(1) A somewhat subtle issue of interpretation that seems invariably to get muddled in the broader public discussion is that we have estimated “the overall effect of IMPACT.” It’s not really possible to do that given that IMPACT went to scale district-wide and at once (it’s an experiment with a sample size of just 1!).

Our inferences are instead based on comparing the outcomes of teachers close to the rating thresholds (i.e., those with big, plausibly experimental incentive contrasts). There are at least two reasons this comparison differs from the “overall effect of IMPACT.” One is that all of these teachers are subject to IMPACT so any shared effects of this policy regime are washed out. Second, our inferences leverage only those teachers whose initial ratings placed them “close” to these thresholds. So, we can’t rule out the hypothesis that teachers who are consistently average in their measured performance perceive neither a threat of dismissal nor the lure of performance bonuses (i.e. IMPACT may have no effect on them). Interestingly, the recent redesign of IMPACT’s performance band appears designed to target the thick band of “effective” teachers.

Anyway, this interpretative issue (overall effects of a policy vs. effects of incentive contrasts within a policy) may simply be “inside baseball” for academic researchers like me. We try to be exacting in terms of what inferences we are making and we discuss this sort of issue all the time!

From a broader perspective, our results are strongly consistent with the logic model advocated by IMPACT’s proponents (i.e., these types of incentives coupled with the other design features and supports driving teacher performance and positive selection into the workforce). And this study has the imprimatur of credible causal inference (RD designs are coupled with RCTs in terms of the highest evidentiary standards in the What Works Clearinghouse). So, I think the reactions from Henderson, NCTQ, etc. are understandable.

(2) A second misunderstanding I’ve observed (possibly going back to Emma’s WaPo article) is that the study says nothing about achievement. In fact, we find effects on IVA for minimally effective teachers and effects among highly effective Group 2 teachers on their more flexibly designed achievement measure (TAS). Moreover, the results of the MET Project suggest that multiple measures (i.e., like those in IMPACT) are better at predicting future student performance than test scores alone. So, this meme seems off base to me.

I also asked Professor Dee, some other questions about the study, which he recalled began in 2011. “For most of this time, we had no external funding; no financial support (or in-kind) transfers from DCPS. We recently received a small grant from the Carnegie Corporation of NY to support this work and we’re currently seeking other research grants for further studies.”[[6]]

[[8]]8. And potentially dangerous–if it encourages other efforts to use test scores as the chief determinant of teacher effectiveness.[[8]]

[[9]]9. Mary Levy added, “Almost none of the students in Ward 3 schools who are low income live in Ward 3.” A few schools West of the Park, including Wilson High School, draw students from outside Ward 3.[[9]]

[[10]]10. Data provided by Mary Levy[[10]]