Three questions: Who makes the rules for classroom behavior? How much should 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-year-olds get to decide, or should the teacher just lay down the rules? And does it make any difference in the long run?

In my 41 years of reporting, I must have visited thousands of elementary school classrooms, and I would be willing to bet that virtually every one of them displayed–usually near the door–a poster listing the rules for student behavior.

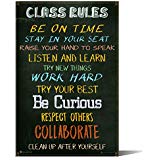

Often the posters were store-bought, glossy and laminated, and perhaps distributed by the school district. No editing possible, and no thought required. Just follow orders! Here’s an example:

I can imagine teachers reading the rules aloud to the children on the first day of class and only referring to them whenever things got loud or rowdy.

“Now, children, remember Rule 4. No calling out unless I call on you.”

There are other variations on canned classroom rules, available for purchase. This one uses a variety of flashy graphics to make the poster visually appealing, but the rules are being imposed from on high, which makes me think there’s little reason for children to adopt them.

I am partial to teachers and classrooms where the children spend some time deciding what the rules should be, figuring out what sort of classroom they want to spend their year in. I watched that process more than a few times. First, the teacher asks her students for help.

Children, let’s make some rules for our classroom. What do you think is important?

Or she might lead the conversation in certain directions:

What if someone knows the answer to a question? Should they just yell it out, or should they raise their hand and wait to be called on?

Or:

If one of you has to use the bathroom, should you just get up and walk out of class? Or should we have a signal? And what sort of signal should we use?

It should not surprise you to learn that, in the end, the kids come up with pretty much the same set of reasonable rules: Listen, Be Respectful, Raise Your Hand, and so forth. But there’s a difference, because these are their rules.

This poster is my personal favorite. It’s from a classroom in Hampstead Hill Academy, a public elementary school in Baltimore, Maryland (and shared by Principal Matthew Hornbeck). You’ll have to zoom in to see the details, which include what to do when working in groups: ‘Best Foot Forward,’ ‘Hands on Desk,’ and ‘Sit Big.’ And there are some things not to do, such as ‘Slouch‘ and ‘Touch Others.’

Another homemade one, entitled ‘Rules of the Jungle,’ makes me chuckle. I can picture the teacher and the children poking fun at themselves while creating a structure to insure that their classroom really does not become a jungle.

The words–Kind, Safe, Respectful–can be found in the store-bought posters; however, the children created the art work and made the poster. It’s theirs; they own it.

The flip side, the draconian opposite that gives children no say in the process, can be found in charter schools that subscribe to the ‘no excuses’ approach. The poster child is Eva Moskowitz and her Success Academies, a chain of charter schools in New York City. A few years ago on my blog I published Success Academies’ draconian list of offenses that can lead to suspension, about 65 of them in all. Here are three that can get a child as young as five a suspension that can last as long as five days: “Slouching/failing to be in ‘Ready to Succeed’ position” more than once, “Getting out of one’s seat without permission at any point during the school day,” and “Making noise in the hallways, in the auditorium, or any general building space without permission.” Her code includes a catch-all, vague offense that all of us are guilty of at times, “Being off-task.” You can find the entire list here.

(Side note: the federal penitentiary that I taught in had fewer rules.)

Does being able to help decide, when you are young, the rules that govern you determine what sort of person you become? Schools are famously undemocratic, so could a little bit of democracy make a difference? Too many schools, school districts, and states treat children as objects–usually scores on some state test–and children absorb that lesson.

Fast forward to adulthood: Why do many adults just fall in line and do pretty much what they are told to do? I am convinced that undemocratic schools–that quench curiosity and punish skepticism–are partially responsible for the mess we are in, with millions of American adults accepting without skepticism or questioning the lies and distortions of Donald Trump, Fox News, Alex Jones, Briebart, and some wild-eyed lefties as well.

Because I agree with Aristotle that “We are what we repeatedly do,” I’m convinced that what happens in elementary school makes a huge difference in personality formation and character development.

Students should have more control (‘agency’ is the popular term) over what they are learning, and inviting them to help make their classroom’s rules is both a good idea and a good start.

As always, your comments and reactions are welcome.

Agreed. Involving young people in helping set the rules makes them feel a greater sense of ownership in, and belief in, the rules.

LikeLike

Well, maybe, John!

It reminds me of when I was talking to a student at Sudbury Valley School. He said, “I’d rather be in an authoritarian military school than in a school in which the teachers let you help decide some of the rules, with them leading the process. I’d rather know who my enemies are!”

So I believe very strongly in real democratic process. In that process I fully expect that the meeting WON’T come up with the same decisions the staff might have made. I believe in my bones (and from experience) that the meeting will come up with BETTER decisions than authority figures or students would make by themselves.

And indeed, yes, our culture has come to crave authority because those students grew up in an authoritarian system. This is much like the Russian public got so used to dictatorship that they had trouble with freedom, and gravitated back to having an authoritarian leader to tell them what to do.

One of my staff members did some research and discovered that voting participation in the United States began to drop as the public school system grew, and it didn’t really correlate with anything else.

I once did a consultation with a school that wanted me to demonstrate democratic process. On the way over I realized that the oldest student was 5 years old! I thought that I would have to create the agenda for them. It was my public school roots speaking to me. When I started the process and explained that a democratic meeting should talk about “what might be a problem in the school, or what might be a good idea for the school” every can went up and the agenda wis instantly made. Among other things they decided that nobody should eat chocolate after the morning because it had a caffeine-like substance in it–this was brought up by a 4 year old. Another 4 year old brought up that he thought that is someone had a cold they shouldn’t go out in the cold. This was passed. I have a video of the whole consultation, called “Pre-School Democracy.” If it doesn’t upen use the code member2016

So I feel you went some of the distance but not all the way there.

Jerry

Jerry Mintz, Director, AERO, http://www.educationrevolution.org

LikeLike

One difficulty many teachers face in urban schools is that diversity can change the rules completely. Many young students today do not recogize rules of any kind. It not only makes teaching more difficult, but it also can make learning impossible.

To make it worse, we are still grouping learners by age instead of needs. Being 8 in grade 3 isn’t nearly as important as knowing how to read in grade 3. Failure to remedy this problem effectively prevents further learning and more chaos.

In short, we need a new design for K12 teaching and learning that focuses more on the learning of each student.

LikeLike

Love the post but can’t find link

You have a very curious list!

Did you see that the president of Harvard University is giving the commencement address to Eva’s 26 graduates? The chair of her board is or was on the Tufts board, where the Harvard president used to be president. I presume her board chair is a billionaire

On Wed, Mar 6, 2019 at 8:48 PM The Merrow Report wrote:

> John Merrow posted: “Three questions: Who makes the rules for classroom > behavior? How much should 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-year-olds get to decide, or > should the teacher just lay down the rules? And does it make any difference > in the long run? In my 41 years of reporting, I must h” >

LikeLike

A more effective method I’ve found over my years of visiting elementary classrooms is the “command presence” of the teacher. The best among them had no need to say a thing. But that was then….

LikeLike

I strongly suspect that most of the rules posters (whether informed by children or by education publishers) become part of the banal background of most elementary school classrooms. At best, they have a life during the first week or so of school, and then fade away. This situation suggests that life without the posters might be enhanced if the posters were retired with ceremony (“you all know and pay attention to the rules; I don’t think you need to see them every day when we can use the space for something more interesting.”)

Then there is room for kids to decide what to post in place of the posters! As for democratic classrooms, teachers and the school administrations should first practice democratic living before asking kids to reflect on what democracy means. Less hypocrisy might lead to more democracy!

LikeLike