I will start with the fun stuff, some grist for dinner and cocktail party conversations about the cost of going to college these days. Then I will try to connect these dots with six interconnected points: 1) The dramatic increase in the number of colleges shutting down; 2) The approaching ‘Enrollment Cliff;’ 3) The growing number of colleges offering three year Bachelor’s Degrees; 4) Increased questioning whether college is worthwhile; 5) President Trump’s attacks on colleges and universities; and, finally, 6) How much if not all of this can be traced back to the policies of Ronald Reagan.

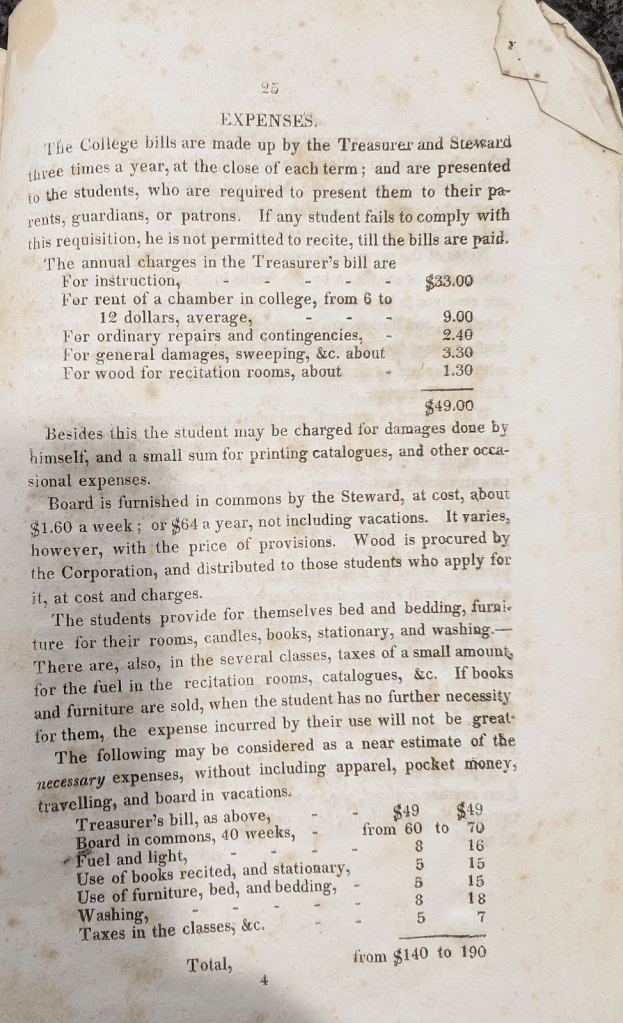

THE FUN STUFF: Two hundred years ago, 1825, it cost less than $200 to attend Yale; this fall it will cost more than $90,500. This includes tuition of $69,900 and a combined cost of housing and meal plans at $20,650. (Simply adjusting for inflation, that bill for $200 would be less than $7,000 today, in case you’re wondering whether the cost of college has gone up a wee bit more than other parts of the economy!)

My brother sent me this from the 1825 Yale student handbook; he also shared it with a grandnephew who is a Sophomore at Yale:

A clever friend of mine reacted with this additional information about life in America 200 years ago: “Those ‘good ole days’ meant a life expectancy of 40 years, an 25-30% infant mortality rate, an annual income of $500-600, and a good bath twice a year, once in the spring and another in the fall.”

A FEW FACTS AND FIGURES: We have nearly 6,000 colleges and universities, both 4-year and 2-year. About 1,900 of these are public institutions, another 1,750 are private and nonprofit, and an estimated 2,275 are for-profit.

More than 60% of today’s high school graduates enroll in college. In the fall of 2024, approximately 19.28 million undergraduate students were enrolled across the United States. Unfortunately, most of them will probably not graduate; in fact, nearly 20% will drop out during their freshman year.

Dropping out is a significant, if largely ignored, issue: Nationally, more than 44 million American adults have some college credits, no degree, and, perhaps, student loan debt weighing them down.

It’s also worth noting that American higher education generally opposed the GI Bill, which allowed millions to attend college, which jump-started the American middle class, and which created a post-war economic boom that lasted for generations.

Another important piece of background information: While most European countries created independent scientific research institutions after World War II, the United States government forged partnerships with colleges and universities. Eventually, the Feds subsidized research at hundreds of American universities to the tune of billions and billions of dollars every year. For years the partnership worked, and the scientific breakthroughs are legendary.

However, there is a down side, because, as the perverse Golden Rule cliché has it, “Whoever Has the Gold Rules.” Every research university has become dependent on those dollars, giving the federal government a powerful hold over higher education. This is, of course, playing out in front of us right now.

Now to the business at hand, my 6 interconnected ideas:

1) COLLEGE CLOSINGS: As noted, nearly 6,000 colleges and universities today, but in 2011, we had more than 7,000. Between 2008 and 2024, two or three colleges closed or merged every month. Today, however, colleges are now closing at an increasing rate–some say it’s one every week! The causes are myriad: Enrollment continues to decline due to natural population trends, operating costs continue to rise, colleges don’t seem to be willing or able to lower their tuition, and young people–concerned about debt–are increasingly skeptical about the value of higher education.

Late in 2024 the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimated that up to 80 colleges could close this academic year because of financial distress caused by a worst-case-scenario drop in enrollment. While for-profit colleges once drove closure rates, since 2020 traditional private colleges have been closing at a higher rate. The closures have affected the lives of more than 50,000 students, thousands of faculty and staff, and the economies of the communities where these institutions are located.

2) THE ENROLLMENT CLIFF: This term refers to changes in the size of the traditional college-going population, 18-24. The so-called ‘Cliff’ that’s fast approaching is generally attributed to a drop in fertility during the Great Recession. “Between 2008 and 2011, the U.S. birth rate plummeted, and despite an economic recovery facilitated within the next decade, did not bounce back. As a result, the college-age population was reduced, and enrollment figures fell from 19.9 million in 2017 to 19.1 million in 2024. Within this time period, public 4-year colleges maintained the most enrollment, totaling 7.8 million students in 2020. Demonstrating the tip of the enrollment cliff, this number dropped to 7.6 million by 2023. Along with declines in demographics, the number of prospective college students may have been impacted by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, in which the switch to online learning led to an additional 1.1 million high school dropouts. Additionally, Americans may be further inclined to defer pursuing higher education on account of the exceedingly high costs – and subsequent debts – incurred from attending college in the United States.”

The Enrollment Cliff gets steeper when one considers the dramatic drop in foreign students. Two years ago, about 6% of all US college students came from foreign countries, more than 1.1 million (tuition-paying) students. This year those numbers are dropping. About half of American colleges anticipate big drops, because the Trump Administration proposes to limit foreign enrollment to 10-15% of a college’s student body.

Meanwhile, a record number of American students have decided to study elsewhere; granted, it’s a small number, but it’s a trend.

While it’s true that college enrollment is up slightly this fall, this is apparently the last gasp, and tough times will soon be upon most institutions.

3) THREE-YEAR BACHELOR’S DEGREES: If you attended college, you spent at least four years earning your degree, but that’s changing. “The first three-year degree programs in the country—online programs at Brigham Young University–Idaho and Ensign College in Utah—gained approval just two years ago. Since then, the number of shortened degree programs has expanded exponentially, with nearly 60 colleges nationwide now offering or working toward developing such programs.”

That’s the lead paragraph of a fascinating article in Inside Higher Education, and I hope you will click on this link to read the entire piece.

When you do, you will discover that almost all of the accrediting agencies (major power-brokers in higher education) are now willing to recognize the 3-year Bachelor’s Degree, something they have resisted for years. Four years and 120 credits have been part of the landscape forever, but just because something is normal does not make it right or inevitable. The 3-year program will require 90 credits, so you can say goodbye to electives, of course. However, if a student is focused on a career, why not push through as fast as possible? Recently a friend told us about his grand-niece, who is majoring in ‘Golf Tournament Management’ at a university in Kentucky. She has to complete internships at three golf clubs during the summers, but why should she have to spend four years on campus?

The same logic applies to graphic design, physical therapy, hospitality management, and cyber-security, and a host of other fields.

It’s also worth noting that higher education systems in some other countries have embraced the 3-year Bachelor’s Degree.

This trend is evidence that higher education is in survival mode, on high alert, perhaps because of #4, below.

4) QUESTIONING COLLEGE: It’s apparent that many young people–and their parents–are questioning the value of higher education in the United States; although 79 percent of Americans believed it was more or equally as important for people today to have a college degree in order to have a successful career, only six percent said that everyone in the U.S. could access a quality, affordable education after high school if they wanted it. In addition, current students have been vocal about the negative impacts of attending higher education, with over half considering dropping out of school due to emotional stress. College dropouts tend to be worse off than when they started due to high levels of debt, and student debt is also a major factor on the financial decisions that Americans can make after college.

5) DONALD TRUMP: He is very much part of higher education’s problem, because he’s not a fan of higher education, and, if you have read this far, I am certain you are familiar with Trump’s attacks on Harvard and other leading private institutions, or his forcing the resignations of the president of the University of Virginia, George Mason University, and others. Under the banners of ‘fighting DEI’ and ‘ending anti-semitism,’ Trump and his allies have seemingly brought most of higher education to heel.

To some extent, higher education has brought some of this on itself, with its embrace of ‘safe spaces’ and ‘micro-aggression’ and ‘identity politics,’ all of which seem to have made many campuses places where it’s dangerous to talk about controversial ideas and even riskier to actually hold divergent views.

Trump’s so-called ‘cure’ may be worse than the disease, unfortunately, but the roots of higher education’s problems can be traced back to another politician who was famously hostile toward higher education, the Great Communicator himself.

6) THE LEGACY OF RONALD REAGAN

If you needed financial help to go to college before Ronald Reagan became president, the chances are you received most of what you needed as a grant, not a loan. From the right-leaning publication, The Intercept: “For decades, there had been enthusiastic bipartisan agreement that states should fund high-quality public colleges so that their youth could receive higher education for free or nearly so. That has now vanished. In 1968, California residents paid a $300 yearly fee to attend Berkeley, the equivalent of about $2,000 now. Now tuition at Berkeley is $15,000, with total yearly student costs reaching almost $40,000. Student debt, which had played a minor role in American life through the 1960s, increased during the Reagan administration and then shot up after the 2007-2009 Great Recession as states made huge cuts to funding for their college systems.”

Here’s more on that point.

And from The New York Times in late 1981: Since taking office last January, the Reagan Administration has set out to curtail the cost of Federal student assistance and to alter the philosophy as well. ”I do not accept the notion that the Federal Government has an obligation to fund generous grants to anybody that wants to go to college,” said Budget Director David A. Stockman in Congressional testimony in September. ”It seems to me that if people want to go to college bad enough, then there is opportunity and responsibility on their part to finance their way through the best they can.”

Most of us have lived through a sea change, going from a time when we collectively believed that investing in higher education paid social dividends that far outweighed the costs, to a time when the federal government and all state governments have reduced their support. Now, the operating philosophy seems to be, “Hey, you want an education? Pay for it yourself!”

I don’t know if anyone has a solution for higher education’s problems, but I am certain that “education reform” is NOT the answer. I see higher education’s challenges as part of a larger picture: our declining commitment to almost anything ‘public,’ such as public transportation, public libraries, public spaces, public schools, public health, public safety, and on and on.

Absent a strong commitment to the common good, coupled with disgraceful–and growing–income inequality, our national experiment in “a more perfect union” seems doomed.